Some people become passionate readers and fans of science fiction during childhood or adolescence. I picked up on sf somewhat later than that; my escape reading of choice during my youth was historical novels, and one of my favorite writers was Mary Renault.

Historical fiction is actually good preparation for reading sf. Both the historical novelist and the science fiction writer are writing about worlds unlike our own. (Here I’m thinking of writers who create plausible fictional worlds that are bound by certain facts, not those whose writing veers toward fantasy.) The historical novelist has to consider what has actually happened, while the sf writer is dealing in possibilities, but they are both in the business of imagining a world unlike our own and yet connected to it. A feeling for history is almost an essential for writing and appreciating good science fiction, for sensing the connections between the past and future that run through our present.

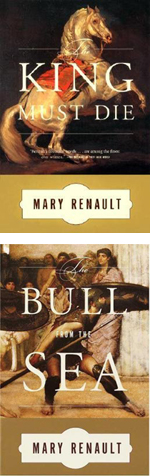

Mary Renault retells the myth of Theseus in The King Must Die and The Bull from the Sea, which should probably be treated as one long novel in two volumes. Reading the first book (which sent me racing to the library to check out the second) as a somewhat messed-up kid in the early 1960s made a powerful impression. The dark, violent, yet alluring culture of ancient Greece combined with an attractive, promiscuous hero was irresistible, but it was the tension between an old (and dying) matriarchal society and the increasingly dominant sky-god-worshipping patriarchal culture that held me. Renault drew on both the writings of Robert Graves and archeological discoveries for her novels, and didn’t make the mistake of importing the mores of her own time to a distant past.

That she was herself a lesbian, and thus an outsider in her own culture, must have contributed to her empathy for the homosexual characters in The King Must Die and The Bull from the Sea, who are depicted largely sympathetically and as part of the normal human spectrum of sexual behavior. Even though Theseus, the narrator, is the center of the story, he is surrounded by a rich cast of strong female characters, among them his mother Aithra, the queen Peresphone, the Cretan princess Ariadne, Hippolyta of the Amazons, and the female bulldancers who are fellow captives with Theseus on Crete. I loved the strength of these women; I wanted to be more like them and less like myself. Identifying with characters may be a problem for literary critics, but it’s standard operating procedure for most bookreading kids.

Looking back, it seems to me now that one of the most important passages in these two novels is the question asked by Theseus’s physician son Hippolytos near the end of The Bull from the Sea: “ I started to wonder: what are men for?” Theseus, used to interpreting various phenomena as expressions of the will of the gods, is taken aback: “I had never heard such a question. It made me shrink back; if a man began asking such things, where would be the end of it?” In the context of the novel, you feel the force of that question, what it must have been like for someone to ask it for the first time. What a distant and alien world, in which such a question could shock, and yet we’re still trying to answer it even as some of us long to retreat into old certainties. Mary Renault may have awakened an interest in both ancient Greece and philosophy in me (my college degrees are in classical philosophy), but I wonder now if that passage pointed me in the direction of sf. Reword the question as “What is intelligent life for?” and it’s a question science fiction continues to ask.

Pamela Sargent’s Seed Seeker, third in a trilogy that includes Earthseed and Farseed, will be published by Tor in 2010. Her other novels include Venus of Dreams, The Shore of Women, and the historical novel Ruler of the Sky, which Gary Jennings called “formidably researched and exquisitely written.” She lives, works, writes, and reads in Albany, New York.